10 Min. Lesezeit

Architektur der Autonomie: Von Prompt Engineering zu zielorientierten Agenten

Jedes Team, das ein LLM-gestütztes Tool entwickelt, stößt auf dieselbe Mauer. Die Demo funktioniert. Die erste echte Arbeitslast jedoch nicht. Das Modell ist nicht das Problem – die Architektur ist es.

Nehmen Sie ein konkretes Beispiel. Ein Unternehmen entwickelt einen KI-Agenten, um seinen ausgelagerten Kundensupport zu ersetzen. Die Demo funktioniert – eine Kundenfrage einfügen, eine Antwort aus der Wissensdatenbank erhalten. Dann leitet das Team das Ticket eines ganzen Tages weiter: 200 Supportanfragen, die von der Auftragsverfolgung über Rückerstattungsstreitigkeiten bis hin zur technischen Fehlerbehebung reichen. Der Agent muss Bestellhistorien überprüfen, Rückgaberichtlinien anwenden, Garantiebestimmungen überkreuzen und personalisierte Lösungen entwerfen. Er versucht, alles in einem einzigen Durchgang zu erledigen, beginnt ab Ticket 50 Kunden zu verwechseln, wendet die falsche Rückgaberichtlinie bei einer Rückerstattungsstreitigkeit an und sendet eine zuversichtliche, aber falsche Lösung.

Frühe LLM-Anwendungen funktionierten wie Funktionen: Eingabeaufforderung rein, Antwort heraus. Wenn die Aufgabe in einem Durchgang und in einem Kontextfenster – der Menge an Text, die ein Modell gleichzeitig im Speicher halten kann – passt, funktionierte es. Aber mehrstufiges Denken, Wiederholungen oder Koordination über verschiedene Arbeitsarten hinweg brechen das Einzeldurchgangsmodell.

Die Lösung ist nicht eine bessere Eingabeaufforderung. Zielorientierte Agenten arbeiten in Schleifen statt in Einzeldurchgängen: Zerlegen Sie das Ziel in Aufgaben, führen Sie einen Schritt aus, prüfen Sie das Ergebnis, passen Sie den Plan an und wiederholen Sie den Vorgang, bis er abgeschlossen ist.

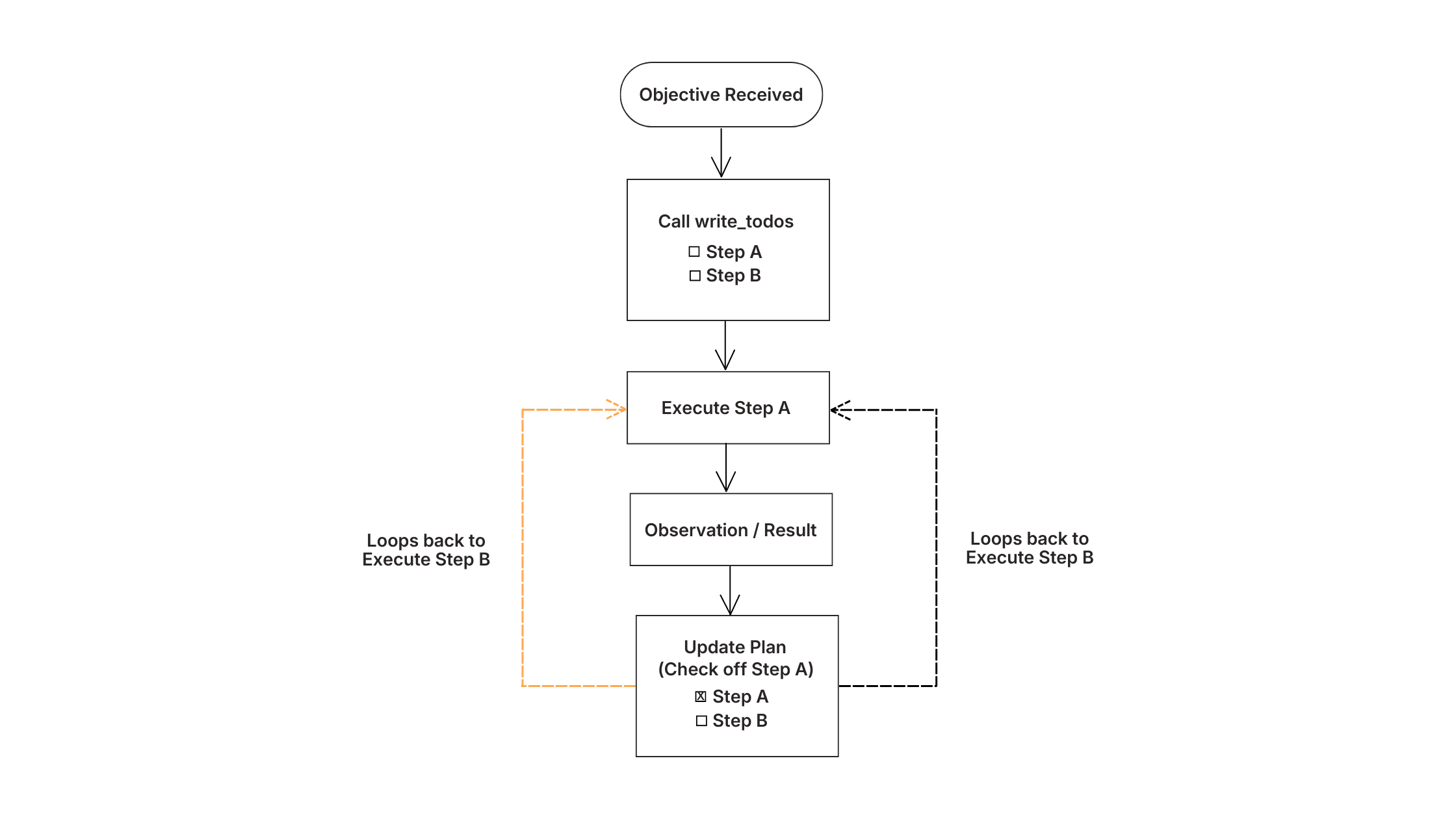

Wie ein zielorientierter Agent ein Ziel verarbeitet: in Aufgaben aufteilen, Schritt A ausführen, Ergebnis prüfen, Plan aktualisieren, Schleife bis zum Abschluss zurücksetzen.

Von Ketten zu Schleifen

Der Support-Agent scheiterte, weil er als Kette gebaut war – eine gerade Linie von Eingabe zu Ausgabe, ohne die Fähigkeit, sich zu erinnern, anzupassen oder zu wiederholen.

Eine Kette ist ein zustandsloses Rohr. Sie verarbeitet einmal und geht weiter. Sie weiß nicht mehr, was sie vor zwei Schritten getan hat, kann den Kurs nicht ändern, wenn etwas fehlschlägt, und behandelt jede Anfrage, als sähe sie die Welt zum ersten Mal.

Ein zielorientierter Agent ist ein zustandsbehaftetes System. Er verfolgt, was er getan hat, was noch übrig ist, und was sich unterwegs geändert hat. Wenn ein Schritt fehlschlägt, passt er sich an. Wenn neue Informationen auftauchen, überarbeitet er den Plan.

Der Unterschied zeigt sich in drei Bereichen:

Wie Entscheidungen getroffen werden. Ketten folgen fest programmierten Schritten, unabhängig davon, was passiert. Zielorientierte Agenten bewerten die Ausgabe jedes Schritts und entscheiden, was als Nächstes zu tun ist.

Wie Informationen gespeichert werden. Ketten halten alles in der Eingabeaufforderung – sobald das Kontextfenster gefüllt ist, gehen Informationen verloren. Zielorientierte Agenten schreiben Ergebnisse in externen Speicher und rufen nur das ab, was benötigt wird.

Wie Arbeit verteilt wird. Ketten führen alles in Reihenfolge durch ein Modell aus. Zielorientierte Agenten delegieren spezialisierte Aufgaben an separate Unterprozesse, die unabhängig laufen.

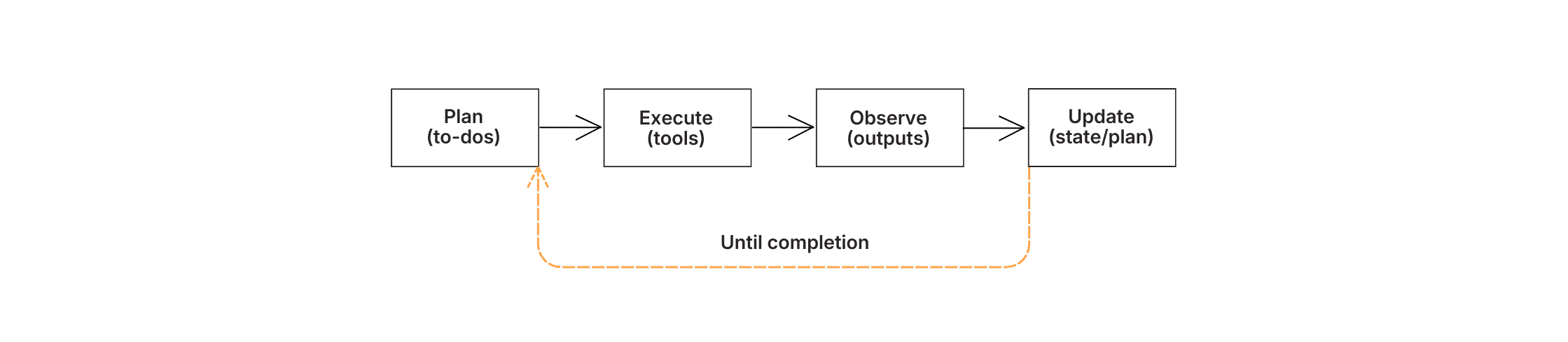

Die Kernidee zur Konstruktion ist die iterative Denk-Schleife. Anstatt anzunehmen, dass das Modell das gesamte Problem mit einem Durchgang lösen kann, entwerfen Sie für die Iteration:

1. Planen Sie, was geschehen muss.

2. Führen Sie einen Schritt aus.

3. Beobachten Sie das Ergebnis – hat es funktioniert? Kam etwas Unerwartetes zurück?

4. Aktualisieren Sie den Plan basierend auf dem, was Sie gelernt haben.

5. Wiederholen Sie, bis das Ziel erreicht ist.

Ohne diese Schleife versucht der Agent, 200 Tickets in einem Durchgang zu lösen und beginnt ab Ticket 50, Kunden zu verwechseln. Mit ihr basiert jede Lösung auf dem Ergebnis der vorherigen.

Plan → Ausführen → Beobachten → Aktualisieren — die iterative Schleife, die es Agenten ermöglicht, selbst zu korrigieren, anstatt sich auf einen Durchgang festzulegen.

Die vier Schichten, auf die Produktionsagenten konvergieren

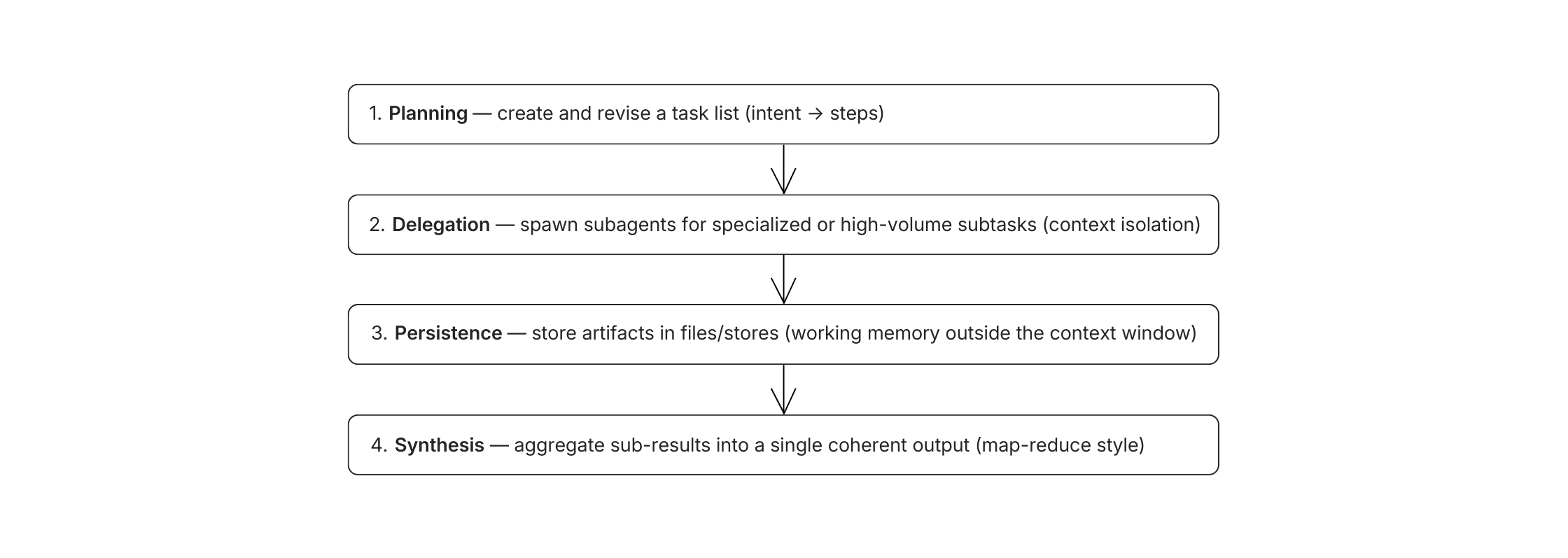

Wenn Ingenieurteams ihre Einzeldurchgangsagenten zu Systemen umgestalten, die im großen Maßstab arbeiten, sehen die resultierenden Architekturen tendenziell ähnlich aus. Über Rahmenwerke und Branchen hinweg tauchen immer wieder vier Schichten auf.

Planung erstellt die Aufgabenliste. Delegation weist Unteragenten zu. Persistenz speichert Artefakte außerhalb des Kontexts. Synthese vereint Ergebnisse.

1. Planung – Absicht von Aktion trennen

Der Agent versucht nicht, alle 200 Tickets auf einmal zu lösen. Er beginnt mit der Erstellung einer Aufgabenliste: Tickets nach Typ kategorisieren, Kundenkonten nachschlagen, Bestellhistorien prüfen, relevante Richtlinien anwenden, Lösungen entwerfen, Eskalationen kennzeichnen.

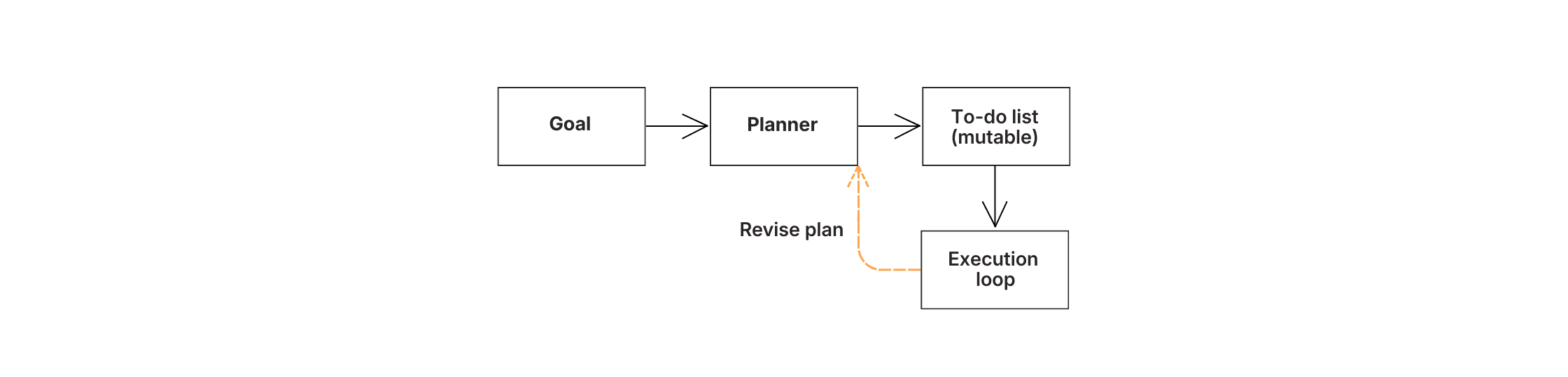

Dies ist Planung – die Trennung dessen, was geschehen muss, von der Handlung selbst. Die Aufgabenliste ist nicht fest. Wenn der Agent entdeckt, dass mehrere Tickets vom selben Kunden zum selben Problem stammen, fasst er sie zusammen. Wenn er auf einen Tickettyp stößt, den er noch nie gesehen hat, fügt er einen neuen Schritt zu dessen Verarbeitung hinzu.

Naive Agenten versuchen, ganze Probleme in Einzeldurchgängen zu lösen. Bei komplexen Aufgaben führt das zu einem Drift – das Modell verliert Anforderungen aus den Augen oder verpflichtet sich frühzeitig zu einem Ansatz, der sich später als falsch herausstellt. Planung verhindert dies, indem sie die Absichten des Agenten explizit und revidierbar macht.

Der Planer generiert eine To-Do-Liste, aber sie ist veränderbar – wenn Schritt 3 fehlschlägt oder neue Infos offenbart, werden die Schritte 4-6 automatisch neu geschrieben.

2. Delegation – Spezialisierte Arbeit an spezialisierte Agenten vergeben

Einem Modell gleichzeitig die Aufgabe zu geben, Kontodaten nachzuschlagen, Rückgaberichtlinien zu interpretieren und kundenorientierte Antworten zu schreiben, überlastet einen einzigen Kontext mit inkompatiblen Rollen. Die Qualität aller drei verschlechtert sich.

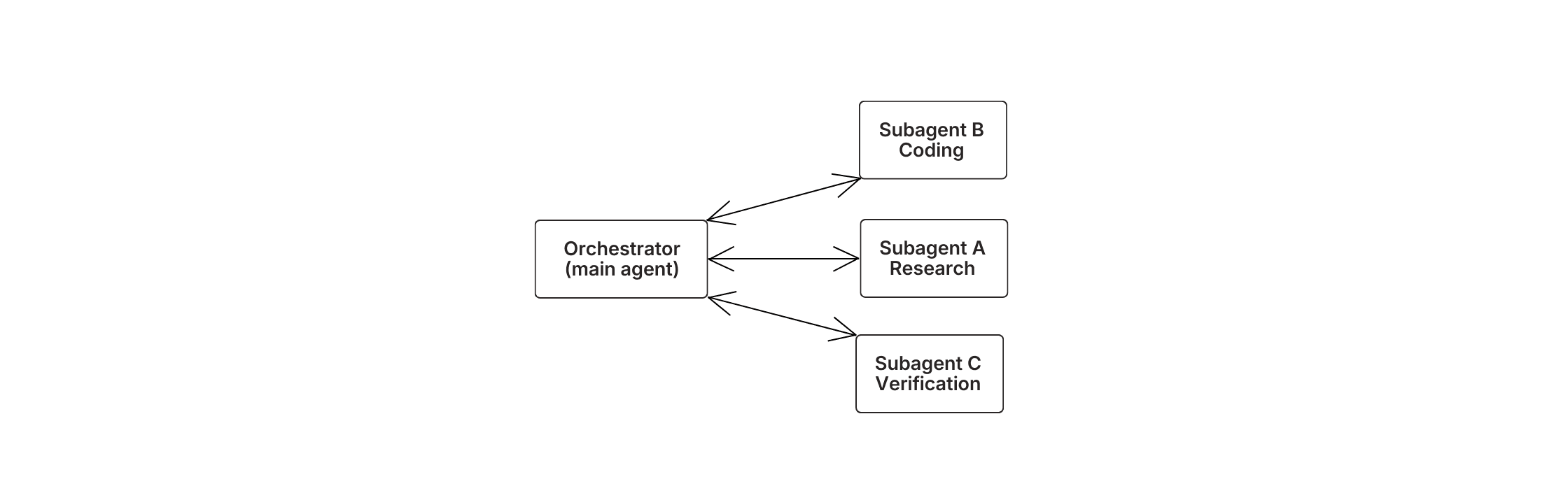

Zielorientierte Agenten lösen dies durch Delegation. Ein Orchestrator – der Hauptagent – hält das insgesamt Ziel und weist umschlossene Aufgaben an spezialisierte Unteragenten zu. Einer kümmert sich um die Kontobefragung und Bestellhistorie. Ein anderer interpretiert Richtlinien und bestimmt die Berechtigung. Ein Dritter entwirft kundenorientierte Lösungen.

Jeder Unteragent arbeitet in seinem eigenen isolierten Kontext, vollständig auf seine spezielle Aufgabe konzentriert. Nur die endgültige Ausgabe fließt zurück zum Orchestrator. Dies hält den Hauptprozess sauber und jede Unteraufgabe fokussiert.

Es gibt einen bemerkenswerten Kompromiss: Wenn Unteragenten parallel arbeiten, ohne Kontext zu teilen, können sie widersprüchliche Entscheidungen treffen. Für Aufgaben, die eine enge Koordination erfordern, funktioniert das sequenzielle Ausführen von Schritten mit komprimiertem Kontext oft besser als das Parallelisieren mit unvollständigen Informationen.

Der Orchestrator hält das Ziel. Recherche, Kodierung und Verifizierung laufen jeweils in separaten Unteragentenkontexten ab, wobei nur saubere Ausgaben zurückgegeben werden.

3. Persistenz – Erinnerung jenseits des Kontextfensters

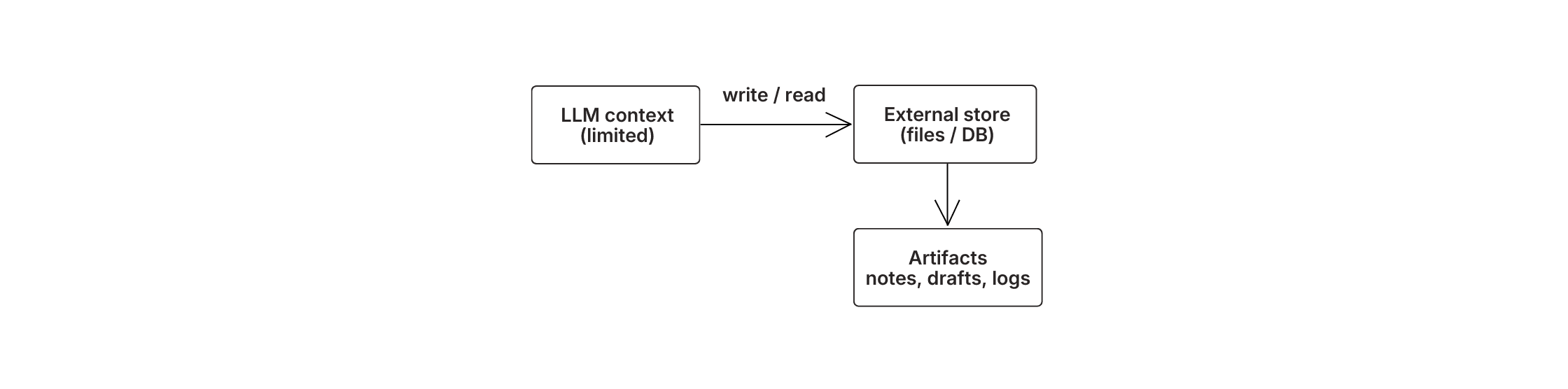

Der Agent muss sich daran erinnern, was er in Ticket 1 gelöst hat, wenn er Ticket 200 bearbeitet. Aber kein Modell kann gleichzeitig 200 Tickets an Kundendaten, Bestellhistorien und Richtlinienabfragen in seinem Kontextfenster halten.

Persistenz löst dies, indem der Agent externer Speicher erhält. Während der Agent jedes Ticket verarbeitet, schreibt er die Ergebnisse in eine Datei oder Datenbank – Kundendetails, Bestellabfragen, Richtlinienentscheidungen, Entwürfe von Lösungsvorschlägen. Wenn er frühere Ergebnisse benötigt, liest er nur die relevanten Teile zurück, anstatt alles geladen zu halten.

Dies entkoppelt die Komplexität der Arbeit von den Einschränkungen des Modellspeichers. Die Aufgabe kann wachsen – 200 Tickets, 2.000 Tickets – ohne dass das Kontextfenster zum Engpass wird. Im Supportbeispiel bearbeitete der Agent 200 Tickets mit derselben Genauigkeit, die er bei einem zeigte, weil jedes Ergebnis extern gespeichert wurde, anstatt in eine zunehmend überfüllte Eingabeaufforderung komprimiert zu werden.

Agenten schreiben Notizen, Entwürfe und Zwischenresultate auf Dateien – dann lesen sie nur das zurück, was benötigt wird, und halten den Kontext schlank, während Aufgaben wachsen.

4. Synthese – Ergebnisse zu einem einzigen Ergebnisausgericht erzeugen

Sobald der Agent geplant, delegiert und die Ergebnisse aller 200 Tickets gespeichert hat, muss er eine kohärente finale Ausgabe erzeugen – nicht 200 getrennte Antworten, sondern eine gelöste Warteschlange mit konsistenter Richtlinienanwendung, eskalierten Markierungen und einer Schichtzusammenfassung.

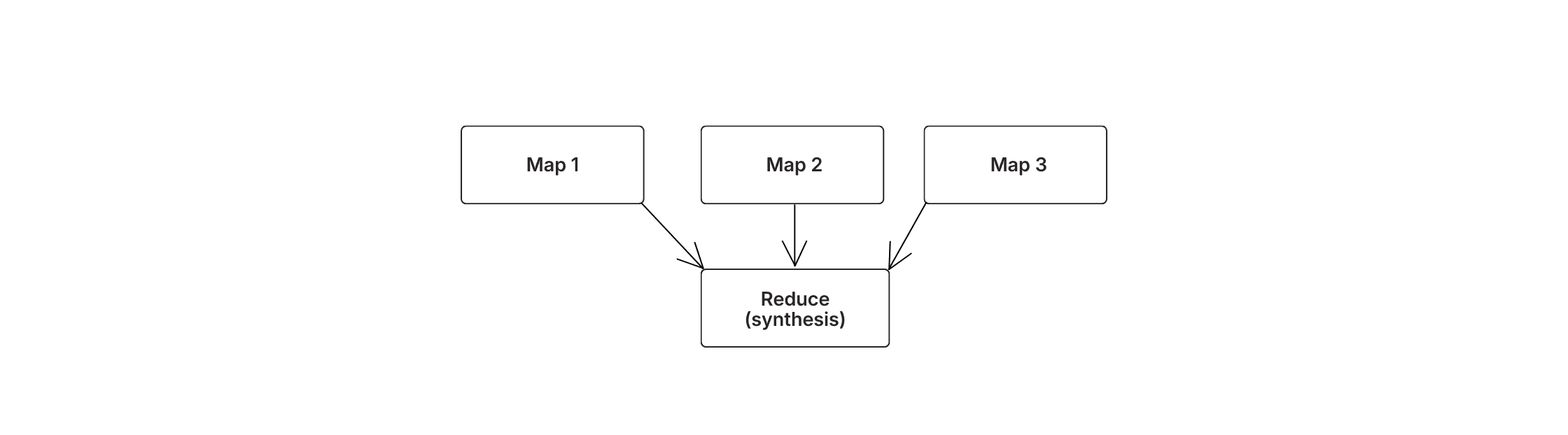

Dies ist Synthese: das Verschmelzen von parallelen Unterergebnissen zu einem einzigen Produkt. Es erfolgt in zwei Phasen:

Map. Jeder Unteragent erledigt seine abgegrenzte Aufgabe unabhängig – sucht Konten, wendet Richtlinien an, entwirft Lösungen. Diese laufen parallel oder isoliert und erzeugen individuelle Ausgaben.

Reduce. Der Orchestrator liest die gespeicherten Ausgaben aller Unteragenten, löst Inkonsistenzen zwischen ihnen auf, identifiziert Muster über Tickets hinweg und stellt die endgültige Warteschlange mit einem zusammenfassenden Bericht zusammen.

Dieses Map-Reduce-Muster ist im Bereich der Datenverarbeitung gebräuchlich und lässt sich direkt auf Agenten-Workflows anwenden. Die Qualität der finalen Ausgabe hängt von allen vier Schichten ab, die zusammenarbeiten – Planung stellt sicher, dass nichts übersehen wird, Delegation sorgt dafür, dass jedes Stück vom richtigen Spezialisten bearbeitet wird, Persistenz sorgt dafür, dass nichts vergessen wird, und Synthese sorgt dafür, dass die Stücke ein kohärentes Ganzes bilden.

Drei Unteragenten führen parallel aus, dann konsolidiert ein Orchestrator ihre Ausgaben zu einem einzigen kohärenten Produkt.

Wo dies gilt

Der Support-Agent ist ein Beispiel. Dasselbe Architekturkonzept gilt für jede Aufgabe, bei der das Ziel bekannt ist, die genauen Schritte jedoch nicht.

Forschung und Analyse. Ein Agent liest Dutzende von Quellen, nimmt Notizen, identifiziert Widersprüche zwischen ihnen und erstellt einen strukturierten Bericht mit Zitaten. Ohne Planung und Persistenz verliert er nach dem fünften Dokument den Überblick über die Quellen.

Codeänderungen in großen Repositories. Ein Agent implementiert ein Feature, das 15 Dateien berührt, führt Tests aus, entdeckt Fehler, behebt sie und iteriert, bis der Build bestanden wird. Ohne Delegation versucht er, die gesamte Codebasis in einem Kontext zu halten.

Vorfallsreaktion. Ein Agent untersucht ein Produktionsproblem, indem er Protokolle abfragt, Metriken prüft, mögliche Lösungen versucht und dokumentiert, was funktioniert hat. Ohne dynamische Planung folgt er einem festen Playbook, selbst wenn die Beweise darauf hindeuten, dass ein anderer Weg erforderlich ist.

Datenintensive Analyse. Ein Agent lädt große Datensätze in einen externen Speicher, berechnet Zusammenfassungen und verfeinert die Frage schrittweise, ohne den Kontext zu überlasten. Ohne Persistenz stößt er bei der ersten großen Tabelle auf Speicherlimits.

Jede dieser Aufgaben bricht unter einer Einzeldurchgangsarchitektur aus denselben strukturellen Gründen zusammen, wie es beim Support-Agenten der Fall war.

Wann man dies nicht verwenden sollte

Nicht alles erfordert einen zielorientierten Agenten. Die Wahl hängt davon ab, wie vorhersehbar die Arbeit ist.

Verwenden Sie festgelegte Workflows, wenn die Schritte bekannt sind. Wenn der Prozess immer gleich ist – extrahieren Sie diese drei Felder, validieren Sie sie gegen dieses Schema, schreiben Sie in diese Datenbank – codieren Sie ihn. Feste Workflows sind schneller, billiger und vorhersehbarer. Sie sind auch leichter auf Konformität zu prüfen.

Verwenden Sie zielorientierte Agenten, wenn die Schritte unbekannt sind. Wenn die Werkzeugausgaben unvorhersehbar sind, wenn sich Anforderungen während der Aufgabe ändern oder wenn Fehler untersucht werden müssen, anstatt sie erneut zu versuchen, sollte der Agent den nächsten Schritt dynamisch entscheiden.

Kombinieren Sie sie. Ein zielorientierter Agent kann einen festen Workflow als eines seiner Werkzeuge einsetzen – „führen Sie die standardmäßige Onboarding-Pipeline für diesen Kunden aus.“ Ein fester Workflow kann an festgelegten Entscheidungspunkten an einen Agenten übergeben – „wenn die Validierung fehlschlägt, untersuchen Sie die Ursache und empfehlen Sie eine Lösung.“

In der Praxis nutzen die meisten Produktionssysteme am Ende beides – deterministische Schritte, wo der Prozess stabil ist, Agenten-Schleifen, wo er es nicht ist.

Was immer noch schiefgehen kann

Selbst gut konstruierte Agenten führen Fehlerarten ein, die in einfacheren Systemen nicht existieren.

Zieldrift. Der Agent optimiert für einen Proxy des tatsächlichen Ziels. Der Support-Agent könnte die Lösungsgeschwindigkeit gegenüber der Genauigkeit priorisieren, wenn seine Erfolgskriterien nicht explizit sind. Minderung: Kontrollpunkte, an denen Menschen Zwischenergebnisse überprüfen, bevor der Agent fortfährt.

Unsichere Handlungen. Ein Agent mit Schreibzugriff auf Produktionssysteme kann Schaden anrichten. Der Support-Agent könnte automatisch Lösungen an Kunden senden, ohne menschliche Überprüfung. Minderung: Berechtigungsgrenzen, abgeschottete Ausführung und Genehmigungsgrenzen für Aktionen mit hoher Auswirkung.

Speichergefahren. Wenn der Agent sensible Informationen in externem Speicher speichert, müssen Retentions- und Zugriffsrichtlinien von Anfang an gestaltet werden. Was der Agent sich merkt – und wie lange – spielt eine Rolle.

Bewertungsblindstellen. Einfache Durchgangssysteme sind einfach zu testen: Eingabe, erwartete Ausgabe, bestanden oder nicht bestanden. Agentenschleifen, die über Dutzende von Schritten über mehrere Unteragenten hinweg laufen, sind schwieriger zu bewerten. Betrachten Sie die Beobachtbarkeit – protokollieren Sie jede Entscheidung, Handlung und Ergebnis – als Anforderung von Anfang an, nicht als nachträglichen Einfall.

Die Architektur ist das Produkt

Der Support-Agent, der bei 200 Tickets versagte, brauchte kein besseres Modell. Er benötigte Planung, um die Arbeit in Schritte zu unterteilen, Delegation, um unterschiedliche Arten von Lösungen zu bearbeiten, Persistenz, um das Gedächtnis über Tickets hinaus aufrechtzuerhalten, und Synthese, um eine kohärente Ausgabe zu erzeugen.

Zielorientierte Agenten wenden standardmäßige Ingenieurideen – Zustandsmanagement, Steuerfluss, Modularität, Beobachtbarkeit – auf LLMs an. Sobald Sie Planungsschleifen, werkzeuggestütztes Gedächtnis und Delegation übernehmen, hört das System auf, eine Eingabeaufforderung zu sein, und beginnt sich wie ein Programm zu verhalten, das Ziele verfolgen kann.